Buddhist Path Society Launches

If you have missed Dharma Cowgirl, please check out my new project, Buddhist Path Society.

The last year and a half has been exciting, but my break from blogging was much needed. As many know, I moved from California to New York and started a new position with a new university. Following the submission of my dissertation, I also simply needed a break from writing. I needed rest and time to re-balance my life.

Now that we are settled in happily in Rochester, I feel a new energy coming into my writing, both in my scholarly work and the reflective style of writing I have shared so often on these blogs.

That energy has taken a new form and you can be a part of it by following, participating in, and supporting the Buddhist Path Society on Patreon. Join me for the journey starting on January 1, 2020!

Anti-Assimilation

‘Diversity’ by Jens Hoffmann via Flickr.com

I’ve been thinking about the word “assimilation.” The preferred outcome for immigrants in the U.S. once was that they would “assimilate” into some (mythical) homogeneous American culture. However, assimilation has never been a force for good in my life. I was arguably raised in that “normal” culture that people want others to assimilate into. Yet, most of the decisions that have brought me happiness have been contrary to the norms of that culture: from refusing to wear shoes as a child, to moving across the country as an adult, to choosing a religion and career beyond the expectations of my culture and family of origin.

In my travels, the more I have learned about other cultures and the more I have adopted the traits of other cultures that I myself have witnessed and judged to be good and beneficial, the better my life has become. I’m not talking about cultural appropriation here, which is superficial and ultimately in service of some privileged ideal of the dominant culture. (Although I’m not claiming I’m immune from that, so please point to it where you see it and I’ll try to do better.) I’m talking about learning how to live well by benefiting from thousands of years of global trial and error from billions of living examples.

So I’m wondering, what is the opposite of “assimilation?” The thesaurus let me down here, because assimilate has other positive meanings, such as to fully comprehend information. There are antonyms for that, but no antonym for the process of learning through difference. Perhaps, “diversification” is the closest we can get to an antonym with a positive connotation.

No matter how much we try to fight diversification and enforce conformity to the mythical ideal, the dynamic forces of different ideas and different ways of doing things that arise when different cultures meet has always been one of the best things about humanity. Historically, places where this happens – trade cities and ports, immigrant communities, verges and borders – have always been hives of innovation and new thinking. They have also been point sources for conflict. Sometimes new ideas and different ways of doing things are simply not compatible with one another, but I don’t think that’s what actually sparks the conflict. The conflict happens when one group tries to impose their ideas and ways of doing things on another. We can look at the entire history of colonialism to see how poorly that worked out. Yet locations where difference was tolerated or prized, even for short periods, flourished and grew. Think of New York City, Hong Kong, or Amsterdam.

Personally, whatever is the opposite of “assimilation,” I want to do that. Whatever that is, it has been a force for good in my life. Japanese manners, Korean food, Chinese subtlety, British humor, Scottish fatalism, Swiss environmentalism, French sangfroid, Latin familia, whatever of these I can integrate into my staid, repressed, pragmatic Midwestern upbringing, the better. The more different examples I have of living well to draw upon, the more opportunities I have to get it right.

I realize I’m getting it wrong. Whatever I admire in my multicultural friends and seek to learn from and adopt into my own life, I’m getting it wrong. Everybody makes lots of mistakes when they’re learning something new. I’ve only really touched the surface of these qualities. I run the risk of essentializing, fetishizing, and appropriating, but I’m trying to do better, to understand deeper, and that, too, is a force for good in my life.

I have not abandoned my culture of origin. There are many things I admire about the way I was raised. My ancestors got a lot of things right, too. I want to preserve that and pass it on. But there are two myths I will always refute. First, they got a lot right, but they also got a lot wrong. My ancestors and my culture (that is, the one I was born and raised with) are not perfect. Nor are other cultures. There are things I admire in every human society I’ve encountered, but also things I don’t understand or dislike. Adopting what is beneficial and what works for me requires critical discernment. Second, adding to who I am doesn’t subtract from who I was or who we are. Learning is not a zero sum game. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. That’s why it is that force for good in my life and the lives of so many others.

Remember Roller Coasters Repeat

‘Hersheypark’ by robert burakiewicz via Flickr.com

This weekend I watched all five of the movies in the Twilight saga. Twice. I loved them. Yes, I understand their flaws. They’re like mental junk food that I don’t feel guilty for enjoying them.

But today at work, I’m still obsessing. I honestly want to go home and watch them again, or read the books again. Or find something else, another book or television show or movie equally emotionally intense.

This is not normal. This is interfering with my work. And I recognize it, though it’s a pattern I believed I’d outgrown with maturity and discipline. I’d also previously associated it with being stressed, depressed, and/or lonely. Now I’m not entirely sure what it is.

I started the month of June relatively content to walk the dog, write, and putter around the house. I confined my consumption of media to a few non-fiction books and television in the evenings. However, as the month progressed, I noticed a trend towards the memoir over the other books and more hours spent in front of the television.

This weekend, after Colin left to visit his father in California, I fell down the rabbit hole. I mainlined the final seasons of the show I’d started earlier in the week. When that was over, I ping-ponged between trying new series in which I was not yet emotionally invested and returning to reruns that I knew I enjoyed but now found a little stale.

That’s when Twilight popped up in my recommendations. I’d read the books years ago at the suggestion of my father, who has a broad taste in media that includes the perpetual 12-year-old girl, while also being a 67-year-old man who loves football and action movies. I even went to the first couple of movies with him in the theaters, before I moved away. I remember snort-laughing inappropriately when the main rival for the affections of the heroine unnecessarily removes his shirt in what I’m certain was intended to be a major new romantic plot twist that everyone saw coming from the start. I never had any interest into seeing how the others turned out until this weekend.

I took advantage of my newfound free time and empty house to indulge my whims. I still snorted and laughed at the most serious moments. The (perhaps accidental) psychological allegory about gender relations stood out loud and clear. My inner feminist could write several posts critiquing individual scenes. But I also smiled most of the way through them.

I thought, perhaps naively, that would be the end of this little binge. I’d get it out of my system, become bored of junk food, and welcome a run in the cemetery, errands, some writing, or chores. Nope.

Why am I so attached to this? Where is this craving for emotional intensity coming from? What is it really seeking? And how do I get back on track?

It’s all the more confounding because I’m not an emotionally intense person. I can get worked up, especially around someone I care about and trust, but the vast majority of the time I keep a fairly even keel. I avoided practically all forms of teen drama growing up. I can handle the most fraught professional meetings with reserve and aplomb. I can calmly hold space for stories of trauma and deep suffering.

But throughout my life I have often craved emotional intensity from other sources and usually turned to fiction to satisfy those cravings. And when I say craving, what I’m really talking about is addiction.

I get addicted. In college, I had to go sober from novels. I couldn’t start a novel and then put it down to go do other things. I’d skip homework, then class, then work, until the book (or stars forbid, the series) was finished. Better to go cold turkey while the semester was in session and limit my binging to breaks. After the advent of Netflix and streaming television shows, I had to put some pretty strong restrictions on that, even going so far as asking Colin to put a pass-code lock on the television for a while.

The last real struggle I had with this was in November and December of 2016, as I approached the deadlines for the qualifying exams for my doctorate. We traveled for Thanksgiving and I chose a novel to reread on Kindle during the flights. Rereading and reruns are often “safer” than new media, less addictive. No such luck this time. That novel was the first in an eighteen-book series (which I’d already completely read, for all the good that did me).

I suffered a major setback ahead of my February deadlines and Colin got to witness his first stress-induced meltdown, which I’d always managed to keep private before. I attributed that incident to an anxiety-fueled need to escape from the pressure of exams (which I was completing while working full-time and teaching part-time). With Colin’s support, I managed to pull it back together, pass my exams, and not repeat the incident during my dissertation.

Prior to the incident during exams, I hadn’t had one like that since shortly after moving to California (2010/11) and never with so much on the line or so much on my plate at the same time. However, I recognized the pattern from my years in the college of architecture, where it had often disrupted my design projects and even interfered with my ability to complete graduate school (before I changed my life path to become a chaplain). I likewise attributed those incidents to stress, isolation, and the final one to burnout.

There may be a link to stress in the chain of causation. As I’ve gotten better at managing my own stress, incidents have certainly decreased and also become less intense and easier to recover from. I attribute much of this to my Buddhist practice. Which leaves me all the more perplexed today.

Is this something hormonal? Something to do with chemical balances of neurotransmitters? Is it some kind of cyclical brain disorder? Is there an unacknowledged source of stress or dissatisfaction in my life I need to address?

And, perhaps most importantly, regardless of cause, what do I do about it? Is this just something I have to ride out? Are their better mental techniques to cope with this? Should I seek a professional? Maybe I just need to spend more time around real people?

Most of the diagnostic guidelines in the DSM for mental disorders include the criteria “interferes with everyday functioning” (or something similar) for a specified period of time, usually for longer than a couple of weeks. When does my little addiction to emotional intensity rise to that level?

I’m still going to work. I’m not staying up all night. I’m eating and showering and I went grocery shopping yesterday. But it’s clearly at a reduced level of functioning. It’s harder to focus and I’m missing steps here and there.

Another thing my Buddhist practice improves is awareness of my own mental/emotional state, so when I’m obsessing over something I can see it quite clearly. Often I can intervene, especially when it’s my own life circumstances that get me upset, but this is different somehow. It feels more like being under the influence of a drug or a hormone induced mood swing (ladies who’ve had trouble with birth control will get me on this one). It feels like an external force acting on me and less within my realm of control than my own emotional reactions to events generally are.

Nor does this feel like just another attachment I can put down. I’ve successfully let go of all sorts of things using Buddhist training. I’ve opened my fingers, but the damn thing’s glued to my hand.

Writing about what is going on can often bring new clarity or create new directions. It’s how I let go of or see through what’s troubling me. Writing about this just seems more documentary than anything. Twelve-hundred words in and I’m no closer to a solution than when I started, though there is catharsis in laying it out so plainly.

I would guess that this incident has been gaining ground since late June and is now reaching a new level in mid-July. I’m not entirely sure how long it will continue, but based on previous patterns, I expect it to lessen by early August.

Meantime, I’ve thankfully little on my plate aside from work. If I wanted to queue up Edward and Bella and Jacob for a third run at this supernatural love triangle tonight, there’s no reason I couldn’t or even shouldn’t really. (Except that Colin is home now and it would probably drive him nuts. Our taste in entertainment has never been a perfect match, but this is a whole new level.)

For now, my entire strategy boils down to repeating “Keep it together, Monica” in my head as I try, again, to focus on work. In that way, it’s just like returning to the breath over and over again during meditation. “Keep it together, Monica. Read that email thoroughly before replying. Double check the meetings on your calendar. Prepare your agendas. Go to the gym. Just keep it together during the day.”

In the addiction world they refer to this strategy as “harm reduction.” If you can’t stop drinking, just drink less. If you can’t stop using, just use on weekends or under supervision. (It’s a controversial strategy, so don’t try this at home without professional advice if you have a substance addiction.)

I don’t think the magnitude of my craving for emotional intensity is comparable to what it’s like to be an alcoholic or drug addict. But there are many psychological parallels. In a way, I guess you could say I’m having a relapse.

Mindfulness and various tricks from the panoply of psychological intervention acronyms (CBT, DBT, ACT, or BSFT) help me keep it together. I’m actually not that worried about it yet. The stakes are so much lower this time around, so I’m just watching the situation with curiosity more than anything else. If I kept it together through my doctorate, I suspect I can manage this. (Maybe with help from Stephanie Meyer.)

A Month of Sort-of Solitude

In her book, Quiet, Susan Cain reminds us that for introverts there is little that is more nourishing than solitude.

I needed this reminder. I needed the reminder that the winds of social normativity blow towards extroversion. I can enjoy those winds, and even bend with them from time to time, but they need not steer my course. I am a better, saner, happier, and more productive person when I grow towards my own nature.

Part of my new position in New York is an 11-month contract. This is fairly standard in academia, where faculty and staff typically take months off in the summer when students are away. I chose to take my hiatus during the month of June.

For the past five years, I have worked full-time, taught part-time, and maintained continuous enrollment as a full-time doctoral student. My habitual inclination was to fill this month with personal projects and socializing to establish a network in our new home. But I was also just plain tired.

Thankfully, I resisted that habit. Buddhist practice has helped me develop a more critical awareness of such habits, first by just noticing that I have them, then by discovering where they come from, evaluating their benefits and drawbacks, and consciously deciding what to do about them. This time, I consciously decided to do, well, almost nothing.

I wrote down everything I could or wanted to do during June into a categorized to-do list. It covered many pages. Then I put it away an didn’t constantly refer to it. I used it as a brain dump to judge my expectations for myself and then let go of my attachment to achieving those expectations.

Instead, I gave myself very modest goals: 1) write a little every day, 2) walk, hike, or run a lot every day, 3) eat healthy, and 4) do a chore or two around the house. This is the exact opposite of the usual type of goals I set myself or the type of goal-setting I teach to students. They’re hardly specific or measurable, but that, too, was part of the mental rest I needed.

Being social was nowhere among those goals, though, in theory I ought to have plenty of energy for it. In actuality, I even curtailed my social media use, staying off Facebook during the week, and taking a fast from Reddit towards the end of the month.

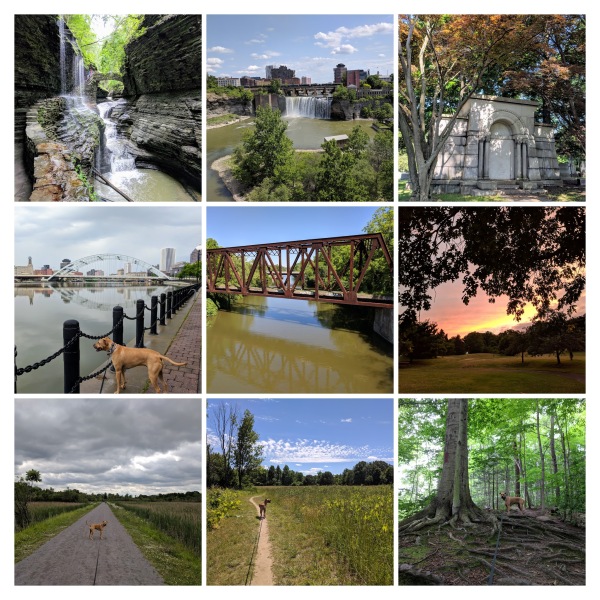

Instead, Archer and I explored the many parks of the Rochester area alone (dogs being a kind of company that soothes introverted senses). We kept mostly to city and county parks, saving the more scenic state and national parks to share with my partner Colin. Archer is learning all the new sights, smells, and sounds of this land, including toads and sing like plucked guitar strings and woodpeckers that sound like taiko drums. We put many miles under out feet and paws.

The many parts in and around our home. Photos by the author. 2018.

Early in the month, I attended a one day teaching and retreat at Dharma Refuge, the Tibetan (American) Buddhist community near our home. I spend a lovely day learning about the 37 bodhisattva practices. But that was enough.

Earlier in May, as my hiatus approached, I had considered spending some of the time in formal retreat, looking at nearby programs for group or solitary practice. Ultimately, I decided against it for financial reasons, but now I think that was the best decision for other factors.

As Buddhists, we are no less prone to spiritual materialism than others. Going on retreat often takes on the quality of “collecting merit” or leveling-up one’s spiritual fitness. We bring an avaricious mindset to the cushion itself. I have seen how just saying there are five levels of something automatically makes me want to achieve them all. This was a chance for me to let go of my attachment to getting stuff done, to goals, and deadlines and productivity.

The idea of going on retreat is to step out of our everyday lives and habitual patterns, to create new conditions conducive to our spiritual lives. Some find it very challenging to create those conditions at home. After all, home is where all the triggers for our existing habitual patterns live.

A habit is composed of three aggregates: 1) a cue to trigger an 2) action that leads to a 3) reward that reinforces the habit. In the morning my alarm (the cue) goes off. I hit the snooze twice and get up on the third alarm, put on my robe, and go downstairs (the action). Then I get my coffee (the reward). This example is simple and easy to spot.

Most habits are not so easy to spot. The subject of money comes up between me and my partner (the cue), I feel embarrassed and uneasy about my financial situation so I act defensively (the action), and we drop the subject (the reward). At first, this doesn’t even seem like a habit. Until I start remembering how money was discussed (or not really discussed) in my family when I was growing up.

Some habits are embedded deep in our subconscious and retreats can help us establish both literal and mental/emotional distance in order to see them more clearly. Yet this is not the only purpose for a retreat nor the only way to achieve this particular purpose.

In fact, for introverts, who are generally (though not always) introspective by nature, sometimes being tossed into an unfamiliar environment with unfamiliar people leads to the opposite effect. We’re so busy learning about this new place and paying careful attention to these new people, that we actually have less time and mental/emotional energy to be introspective.

Solitude, in contrast, is a great opportunity to examine how our habitual patterns play out in our lives, especially our social patterns. That may sound paradoxical, but it’s only when I’ve been by myself for a while that I start to notice how I behave around others. When I’m finally around someone else, it’s like putting on an old pair of shoes that I haven’t worn in a while. The fit is right, but they seem just unfamiliar enough that I notice. I sort to notice all kinds of odd patterns of thought, speech, and behavior I’d previously overlooked and to dig down into their root causes. (This works for extroverts, too, by the way. Though they may prefer smaller doses.)

Solitude does other important things for introverts that retreats are also supposed to do, like recharging and re-centering.

I, like most western Buddhists who go on retreat, usually end up in a small group setting (20-100 people) in some nice rural Dharma center. On the one hand, these kind of retreats are very nourishing. It’s wonderful to be around fellow practitioners and hear and discuss teachings together. The sense of community often gives me a boost.

On the other hand, people are tiring. They just are. And some people, especially strangers, more than others. Occasionally, I even want the people I love most to just go away because they’re, well, people.

Solitude is, happy sigh, almost inexpressibly delightful in contrast, especially given that I have a people-focused job the rest of the year. And that delight reminds me of many of the things I value most and energizes me to return to my work.

The Dharma instructs us to serve others and to value others as equal to or above ourselves. I can’t really tell if this last month has been about self-care in service of others or simple self-indulgence because it felt good. It’s probably a bit of both. My motives are far from pure, but I hope they’re generally moving in the right direction.

I don’t think introversion is inherent to my nature. It’s just a quirk of how this brain, body, and adrenal system are wired, a cause and condition of my aggregates. Even within this life, it is subject to change. I’ve become far more extroverted as I’ve aged.

Please don’t mistake my discussion of introversion or extroversion as reifying some false self concept. I put it about on par with saying I have thick wavy hair. I had to learn how to take care of my hair properly as I got older. Different hair needs different things. So do different brains.

I hope introverts also learn how to take care of themselves and tailor their Buddhist practice accordingly and free from guilt. Group practice is wonderful, but so are long walks in the woods. Chanting, rituals, and empowerments can be sublime, but so can wandering in wetlands with no particular agenda.

We need to learn about one other with a splendid urgency, but we also need to learn about ourselves. So enjoy a little solitude now and then, if you can, introverts and extroverts and ambiverts alike. And a good walk with a trusty dog.

The Karma of Compassion (or Forgiveness)

‘You give love a bad name (now with added robin!)’ by id-iom via Flickr.com

“So what is the Buddhists understanding forgiveness and mercy?”

That was the gist of the question I received in a public conversation on religion this week.

“Well, first, there is no the Buddhist understanding of much of anything. Buddhism is an extremely diverse religion,” I started. “But in general, forgiveness and mercy are not words you will hear often from Buddhists or in Buddhist writing. The sentiment is certainly present, but expressed differently.”

I spoke instead about compassion. We sat is a small circle of chairs, so I tried not to make it into a Dharma talk or a lecture. Instead, I spoke of my own struggles to come to terms with those who had harmed me.

Before I can extend compassion to the one who has harmed me, I must first extend compassion to myself for the harm done. (I’ve tried it the other way round and it just doesn’t work.) I must pop the bubble of my egoistic delusion that I am unassailable. I must admit that my Buddhist practice is not yet so advanced that insults to my pride do not sting or that I do not sometimes wish misfortune to befall those who irritate or hinder me.

“Let’s say, to put it bluntly, that someone screws with me,” I told the gathered group. “What do I do with that?”

I realized later, the choice of language was telling, though perhaps not obvious. What do I do with that? Not about that or about them, but with the situation and my response to it.

Usually, when we are wronged, we jump straight to a response. ‘Ef, with me, will you? I’ll ef you up!’ or something along those lines.

But Shantideva advised,

When the urge arises in your mind

To feelings of desire or angry hate,

Do not act! Be silent, do not speak!

And like a log of wood be sure to stay.– Bodhicharyāvatāra 5.48

Do not act on anger, irritation, mockery, pride, arrogance, envy, or jealousy, Shantideva warns us. Instead,

Examine thus yourself from every side.

Take note of your defilements and your pointless efforts.

For thus the heroes on the Bodhisattva path

Seize firmly on such faults with proper remedies.– Bodhicharyāvatāra 5.54

The buddhadharma is filled with such remedies. The one that work best for me are compassion and patience. For others, it may be loving-kindness or equanimity or wisdom.

Shantideva tells us not to act from these poisonous emotions, but he does not say they are unwise or that we ought do nothing at all. Instead, we must examine them. Where do they come from?

Anger can point us in the direction of injustices to be remedied. But it can also just as easily point to our own thwarted selfish desires. Pride can point towards our skills, which we can use to benefit others. But it can also just as easily point towards delusions we hold about ourselves and others.

Thus, take note of your defilements and your pointless efforts. Do not act if it is pointless! Act where you can do good, starting with yourself! (But don’t stop there, for humanity’s sake.)

When someone has harmed me, I must first acknowledge the harm, acknowledge that I am vulnerable, and acknowledge that often this is a good thing. We are vulnerable because we are interconnected and because phenomena are impermanent.

Change is very good news. Because of change, enlightenment is possible. Hurt and suffering are possible, too, but so are joy and nirvana.

I must acknowledge that I have been harmed. I have been struck by an arrow. And then I have compounded my own suffering by being angry at the person who shot the arrow, by railing against the unfair circumstances that allowed me, me!, to be struck, by resisting anyone who wanted to pull the arrow out, afraid that it might hurt more.

Naturally, I have a good rant against my attacker in my head (or not so silently). They are stupid and mean and selfish and every bad name in the book. And they are also suffering.

When I acknowledge my own suffering, I can start to see the suffering in others, the suffering all around me. When I turn away from my own suffering, I turn away from the suffering around me.

I breathe in and acknowledge the suffering. I breathe out and wish myself liberation from suffering. Then, I feel better. Slowly but surely, I feel better, and slowly but surely, I see their suffering also.

When our suffering is acute, it is hard to see suffering in others. We must clear the air around ourselves before we can see even into even the near distance.

I told the story of Angulimala, the mass murder who tried to kill the Buddha. Angulimala chased the Buddha, but could not catch him, and called out for him to stop. The Buddha replied,

“I have stopped, Angulimala. You stop.”

…”I have stopped, Angulimala, once & for all, having cast off violence toward all living beings. You, though, are unrestrained toward beings. That’s how I’ve stopped and you haven’t.”

– Angulimala Sutta, MN 86, Access to Insight

When I first learned of this story, it usually ended with Angulimala renouncing his murderous ways, becoming a monk, and achieving enlightenment. When I read it for myself, I realized, the story doesn’t end there.

First, the king comes with soldiers and chariots to kill the murderer Angulimala, but the Buddha talks him out of it. The words forgiveness and mercy are not used in this passage (or their equivalents), though clearly the king had every legal right to execute Angulimala and, seeing he was now entirely peaceful, chose not to.

So Angulimala remained with the Buddha and, no longer focused intently on his mission to kill, began to see the suffering of people all around him. He learned from the Buddha how to wish for their wellbeing.

But although his intentions had been purified, he could not undo what he had done in the past. The suffering he had inflicted on others followed him. They suffered grief for lost loved ones, fear for their own lives, and anger towards him. And even though he was now a monk, wearing a monk’s robes, they assaulted him.

Then Venerable Angulimala, early in the morning, having put on his robes and carrying his outer robe & bowl, went into Savatthi for alms. Now at that time a clod thrown by one person hit Venerable Angulimala on the body, a stone thrown by another person hit him on the body, and a potsherd thrown by still another person hit him on the body. So Venerable Angulimala — his head broken open and dripping with blood, his bowl broken, and his outer robe ripped to shreds — went to the Blessed One. The Blessed One saw him coming from afar and on seeing him said to him: “Bear with it, brahman! Bear with it! The fruit of the kamma that would have burned you in hell for many years, many hundreds of years, many thousands of years, you are now experiencing in the here-&-now!”

– Angulimala Sutta, MN 86, Access to Insight

Angulimala bore with it because he saw that these people were also suffering. In time, he attained enlightenment and release from all suffering. And this story has been used by Buddhists for centuries to teach forgiveness, mercy, and redemption.

Whether we believe in the fires of hell or not, we can see the suffering caused in the here and now. We feel our own suffering keenly and we begin to notice the suffering of others.

It has always helped me to remind myself “Hurt people hurt people.” Suffering begets suffering. This does not excuse it (we cannot escape our karma), but it clarifies a chain of causation that needs addressing.

It helps me have compassion. When I have compassion, I suffer less, I act more skillfully, and I do not compound the situation with further anger.

Then, I can often reach out and help alleviate the suffering of the person who hurt me, not immediately, but after I have first had compassion for myself and developed a bit of calm and insight. When their suffering is addressed, they do less harm to me and others. They may even work to redress the harm they have already caused.

This is why patience is often described as the antidote for anger. In order to serve as an remedy, it has to be an active sort of patience. It is patience that does something. While outwardly, we remain like a log, inwardly we are working hard, applying the antidote to the poison.

To use active patience, sometimes we need time and space in which to work. We remove ourselves from the immediate situation and return after the antidote has neutralized some of the previous animosity. I prefer to go home, take a shower, take a nap, take a walk around the block with my dog, sit is stillness and silence for a bit, sleep on it, maybe write about it, all the while breathing in my suffering and breathing out compassion for myself, then compassion for others.

It is important to have healthy boundaries and a keen ability to spot when we have been harmed. This is not always easy, because some of us (myself included) like to think we are invulnerable. Other people tend to think they deserved the harm and so should excuse it. Neither idea is skillful. Healthy boundaries help us know when harm has been done and prompt us to start considering how to both protect ourselves and deal with the perpetrator. But this is another blog post in what has already become quite a long reflection.

Religions play an important role in teaching us how to respond skillfully when, to put it bluntly, someone screws with us. Almost all religions call for some manner of forbearance. Call it forgiveness and mercy. Call it compassion and loving-kindness. Call it remaining like a log!

These teachings are wise in a way not immediately obvious. We think we ought to forgive altruistically or have compassion altruistically, but in my experience, I have compassion because it reduces my suffering first. Maybe that’s selfish, but that’s just how it works. As my suffering is alleviated, I am better able to help others and more inclined to do so. That’s the karma of compassion, the chain of causation it sets in motion. And this, in my opinion, is a very good karma.

My Little Known Self

“There was a hole in the wall. It’s gone now” by Sergio Y Adeline via Flickr.com

Yesterday was a good day. I slept, ate, worked, socialized well. Then around 8:30 p.m. for inexplicable reasons, I was grumpy. Colin and I were having a conversation and everything he asked was irritating, the way he ate his pasta was obnoxious, the effort involved in getting ready bed seemed like a giant burden. I was just grumpy.

Maybe I’m just toddler-ed out, I thought. You know when you see a toddler in a supermarket who was happy one second and then suddenly they’ve depleted their energy reserves and they’re tired and they want to be done and can’t handle their own existence anymore? Like that, but for adults coming at the end of a full day.

I tried to be as transparent as I could with Colin. I knew it didn’t make any sense. How can anyone eat pasta obnoxiously anyway? He took it with aplomb and I got ready for bed.

This morning I’m still grumpy. My mind is discursive and dwelling far too frequently on the negative and the unknown, whereas int he prior two days I felt positive and energized for everything I had to do.

Yesterday over lunch I watched a TED talk by Tim Harford about complexity. We actually know so little about how things work, he argues. Mostly we got here by trial and error. We find out what works by finding what doesn’t work, but most of the time, we don’t know why one thing works and one thing doesn’t. We know so much less than we pretend we do.

I feel that way about myself. I really don’t know how my self works. I mostly get along by trial and error. Right now, I suspect I’m under the influence of a swing in hormones or fluctuation in neurotransmitters, but I really don’t know. Maybe my immune system is fighting a virus? Maybe I was subconsciously psychologically triggered by something I read or watched? But I know from experience that getting into a fight with my partner would be an error and going to bed will probably work out better for us both.

The point is, I don’t know why I was grumpy but I know I wasn’t fully in control of what I was feeling. Something happened and I was just observing it and trying to do as little damage as possible to those around me.

It’s moments like this that remind me of just what a construct the “self” actually is. It’s an aggregate of fluctuating causes and conditions popping in and out of existence over which we really have so little control. It’s not random. It’s just inexplicable.

The “Self” (big “S”) is the idea that we have more control than we think we do. That we understand. That whatever we’re feeling or thinking or doing is somehow validated and justified because it’s “me.” It’s the idea that I have every right to tell Colin off for being an obnoxious jerk and pestering me when I’m tired and he should know better, even though his behavior was no different from any other night or even the hour before.

Little “self” isn’t much of a problem. It’s just a handy label for a collection of phenomena that really have no hard and fast borders. It’s like looking out at a body of water and calling it the Missouri River. You know that the water you’re looking at from one second to the next is never the same and if it dried up it wouldn’t be a river anymore.

Big “Self” can be a big problem when we let it. We buy into our emotions and thoughts, identify with them, create stories around them, act them out among others. We try to hold the river still. When someone dares suggest that our feelings or thoughts might simply be momentary or not really caused by whatever story we’ve made up to explain them, we feel like they’re challenging our very identity – an identity we built. It hurts.

I fall for this trick a lot. I see my “Self” one way and I invest in that. I build walls around it and defend it from attack. But the joke’s on me because I can’t control what’s coming in an out anyway.

Last night it was too inexplicable and I was too tired and maybe this whole anatta thing is starting to sink in, but I just noticed I was grumpy, shrugged, apologized to Colin, and went to bed.

This morning as I brushed my teeth, still grumpy, I wondered about how western psychology and culture reifies the big “Self.” As a chaplain, I’m trained to accept and validate people’s emotional reactions. I meet them where they are, hear their stories, and try to empathize. Sometimes, I’m the first person to really provide that kind of nonjudgmental witnessing and support and it can be immensely healing.

As a Buddhist chaplain, I take it all with a grain of salt. There’s a trick to absolutely believing what someone tells you about their experience while simultaneously believing they really don’t know what’s going on simply because nobody does (including me). It’s about validating their emotions and seeing through them at the same time. It’s about understanding their thoughts and reasoning and knowing that whatever they can put into words is only a fraction of a fraction of the truth behind it.

It’s what Zen Buddhists call the not-knowing mind, neither affirming nor negating, just letting be. It creates a tremendous sense of possibility. Great anger can turn towards forgiveness. Great passion can mellow into deep friendship. Mild grumpiness can be humorous. When we think we know, many possibilities are foreclosed, so I also try to not-know when it comes to myself.

I hold myself in skepticism. My emotions aren’t always justified or valid or useful. They’re just there and they tend to drive my decision making, whether I want them to or not. Sometimes they’re wise and trustworthy, sometimes not. My rational mind is powerful, but tends to operate post hoc most of the time, helping me make sense of what’s already happened. It’s also a big fat liar, trying to explain the inexplicable and justify the ridiculous. Just look up the lists of logical fallacies and cognitive biases to which we are prone on Wikipedia if you don’t believe me.

But you know, once I began to approach myself with that skepticism, it lifted a tremendous weight off my shoulders. I feel so much lighter for not having to invest in my every passing emotion or thought. I don’t have to build those walls around big “Self” quite so high. They’re still there, make no mistake. (I’m still an academic after all, so my whole identity is built on confidently knowing stuff.) But sometimes I get to look at those walls and realize how silly they are.

In Defense of Solitude

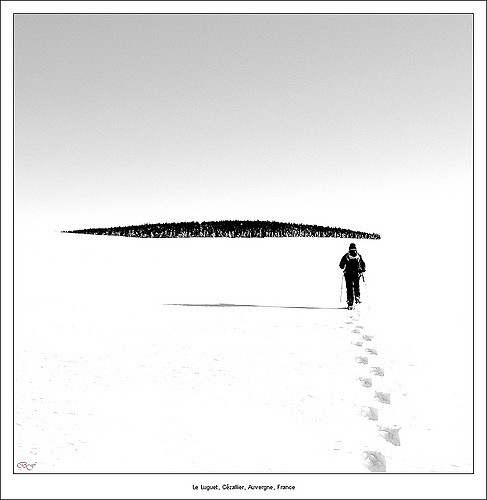

“Solitude” by Dino8 via Flickr.com

The most calm moments of my life come when I am alone. I cherish these moments of calm, still, quiet, undemanding solitude. In a country and culture obsessed with the sadness of loneliness, I want only to be alone for a few moments. To be lonely is a tragedy, but to be alone can be a joy.

For six years, I lived alone. I often traveled alone, in cities and wilderness, and generally enjoyed myself. I often worked in my studio alone, choosing odd hours when classmates were elsewhere. I never compromised on where I chose to eat or sleep, what shows I watched, what music I listened to, what furnishing I bought, how long I sat on a rock in an aspen grove listening to the stream. I never indulged in compromises or permitted unwelcome activities, foods, sounds, or decor. It was not always joy. Sometimes, I was lonely, but on balance, I was content.

Then I moved to California and had a roommate again. As roommates go, he was very low key and I still enjoyed many hours alone most days. He had buddies over late at night to drink and talk, but only on weekends. I learned to sleep with earplugs in. The decor was spare, bachelor-ish, but not unpleasant. He cleaned the house like a machine each Saturday, which benefited me unequally. I was still occasionally lonely and I longed for my own place again, but I was not discontent.

I found a partner and we moved in together about five years ago now. I would not trade our relationship, but since then I have enjoyed less and less solitude. Rarely was I home alone. Errands were often run together. I spent more and more time at work around people. When I traveled, it was for crowded conferences or family vacations, no more solo wanders. Even spiritual retreats were confounded by others.

Yet my spirit, such as it is, never feels so calm, clear, and refreshed as when I am alone. The Buddha needed to be alone for his growth. Hermitages continues to be a vital part of Buddhist tradition, though it is less practiced now for economic and cultural reasons.

Today I experience blessed solitude with something like nostalgia. Like a warm cup of my favorite tea not tasted for many years. It is something to savor and stretch. In such rare moments, I find myself unwilling to do any work or even move around too much, lest I disturb this moment of peace. With regularity, I hope this reluctance will pass and the calm remain.

Colin and I have settled into our new routine in Rochester, which allows me to spend Friday mornings home alone after he has gone off to work. This morning, I spent the time reading on the couch under a pile of blankets, the dog’s head in my lap, watching the snow fall outside our living room windows. I told myself I should get up and work a bit on my dissertation, but I didn’t want to disturb the moment.

We’ve settled into our little old house just south of Downtown. For many years we’ve lived in “open floor plan” apartments. Our last apartment had enough bedrooms that we could each have a separate office, which was delightful. This is the first house we’ve had with a separate living room, complete with a door. We both agree it is preferable. We find open floor plan homes, like open offices, to be overrated. Colin no longer has a separate office, which we agree is unfortunate. He’s taken over the dining space by the kitchen, which is less than ideal, but sufficient in size.

I love people. I love them in their particularity. They are fascinating. I often seek them out and enjoy when they seek me out. I love my family, my in-laws, my partner.

But I also love solitude and separation. Having a little now and then helps me love people more, not less. It gives me time to refresh and reflect and return to them better than I could be had I never been alone.

If you have someone who loves solitude in your life, think of it like a gift you can give them now and then. Like cookies or flowers. And remember, wanting to be alone doesn’t mean they don’t want to be around you. It means they want to be around you in the best way they can. Being alone doesn’t mean they are lonely.*

Perhaps we’re not all built this way, but I am. I can cope with much less solitude than I used to enjoy, but I still crave it and savor it. It’s one of the reasons I enjoy winter. There’s so much more cultural permission for solitude in winter. It refills me for the remainder of the year. I am at my best with others when I have had some time without them, even those that I love the most.

*(Many people in this world are lonely, especially the elderly and those struggling with depression or disability. There are many charities that provide home visitation and, if you love people, consider volunteering for one.)